South Asia’s Quiet Refugee Crisis: Caught Amid Law, Identity, and Climate

I grew up in Guwahati (Assam), where questions of identity were never theoretical. They surfaced in school registers, land records, police verifications, and anxious family conversations. Some people carried documents with them like talismans. Others lived in fear that a single missing paper could erase their place in the only country they had ever known. Long before I understood the politics of migration, I witnessed its emotional cost.

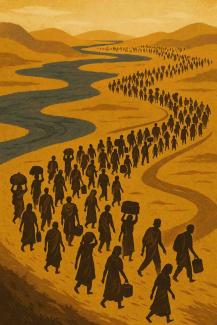

South Asia’s refugee crisis did not end with Partition or the 1971 war. It evolved. Today, displacement is shaped not only by conflict and religious persecution but also by law, bureaucracy, and climate collapse. Across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, refugeehood has become a layered condition, where identity determines protection and legality decides dignity.

In recent decades, thousands of Sikh and Hindu families have crossed from Pakistan into India, settling quietly in Rajasthan and Punjab. Many live in informal colonies, work in precarious jobs, and wait for legal certainty. The Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019 promised relief by offering a pathway to citizenship for non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. For some, it delivered long-overdue recognition. For many others, it exposed a deeper ethical fault line. Why should refugees depend on religion? What of Ahmadiyyas, Shias, and other persecuted Muslim communities who flee the same violence but remain excluded?

A humanitarian problem was acknowledged, but selectively. The result was not just legal controversy, but a redefinition of refuge itself as conditional rather than universal.

Nowhere has the psychological cost of citizenship politics been more visible than in Assam. The National Register of Citizens was designed to identify undocumented immigrants. In practice, it rendered nearly two million people stateless overnight. Many were women without birth certificates, elderly residents who had lived in India for decades, and families whose documents had been washed away by floods. Households were split between those who “belonged” and those who suddenly did not.

For many, life after the NRC became an endless cycle of legal appeals, detention fears, and bureaucratic humiliation. The anxiety did not remain confined to courtrooms. It entered kitchens, schools, and workplaces. Citizenship, once assumed, became something that had to be constantly proven.

The unresolved legacy of Bangladesh lies beneath Assam’s fear. During the 1971 Liberation War, nearly ten million refugees crossed into India. Many never returned. Their presence reshaped politics and demographics in the Northeast. Today, deportation remains stalled. Bangladesh denies citizenship to many undocumented migrants. India cannot repatriate them. The result is a population trapped in legal suspension, unwanted by both sides.

From the ground, this is not geopolitics. It is quiet abandonment.

Yet even this crisis may soon be eclipsed by another that the law barely acknowledges: climate displacement. In the Sundarbans and low-lying regions of Assam and West Bengal, rivers erase villages each year. Rising seas, floods, and erosion force families to migrate, not because of war, but because their land no longer exists. These people are climate refugees in every practical sense. Legally, they are invisible.

Neither Indian nor Bangladeshi law recognizes climate-displaced persons as refugees. Without status, they lose access to welfare, housing, education, and healthcare. As climate shocks intensify, this category of undocumented, unprotected migrants will grow. South Asia is walking into a displacement emergency with no legal language to describe it.

At the individual level, statelessness is not just a theoretical violation. It affects whether a child can attend school, whether a woman can get hospital care, and whether a family reports a crime. Fear of being exposed influences everyday choices. Silence becomes a means of survival. The lack of legal identity results in the lack of a voice.

Despite hosting some of the largest displaced populations in the world, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh remain outside the 1951 UN Refugee Convention. There is no regional refugee framework, no shared standards of protection, no collective planning for climate migration. Refugees are managed as political liabilities rather than human responsibilities.

This must change. South Asia needs a non-discriminatory refugee architecture that is grounded in constitutional values, adaptable to climate displacement, and coordinated across borders. India, by virtue of its democratic institutions and regional weight, can lead this shift. But leadership today requires more than legislative power. It requires moral clarity.

I often return in memory to Guwahati. To the river that swells each monsoon. To neighbors who still keep their documents wrapped in plastic. To families living with the fear that legality can be lost as suddenly as land. The refugee crisis in South Asia is not only about borders and treaties. It is about what happens when belonging becomes conditional, and dignity becomes provisional.

Laws can regulate movement, but they can't determine who deserves to be human. Behind every identity card is a person seeking not just shelter, but a place where they are truly allowed to belong.